Organic Placemaking and the Value of the Unregulated

Whether San Remo, Italy; or York, England; narrow streets, overhanging storeys, and cascading level changes are the hallmarks of medieval townscape. All woven together in an apparently chaotic cheek-by-jowl composition, these are the most loved, the most visited, and often the most valuable parts of our urban realm.

But a look around the good, the bad and the average of city place-making over the last 50 years will lead you to the inevitable conclusion that we don’t make places like that any more. And you’d be right. We don’t… but Brazil does, and so does much of the developing world.

The Rocinha favela, Rio de Janero

In a recent BBC article on the rich cultural life in the Rocinha favela, this video of a moto-taxi ride through the Rio de Janero slum shows the dramatic urban form and grain. Watching this, it’s impossible not to be struck by how this 20th/21st century piece of city has so much in common with the medieval old-towns we know and love.

Rocinha may be built quickly in cheaply available concrete and corrugated sheet metal but the character of the architecture – and the vibrant street life that comes with it is every bit the equivalent of Edinburgh or Tallinn.

The development of favelas is largely unofficial, unplanned and outside of the rules, – much like the development of cities in the days before building codes were codified. This lack of over-arching regulation left room for growth, change, small scale intervention, and adaptation to the wants and needs of everyday life and trade. It’s this organic growth process, both in city-life and in built fabric, that creates the unique character and feel that these places have. They resonate with a natural sense of order and complexity. They are scaled at a human level because their development is born of human scale decisions.

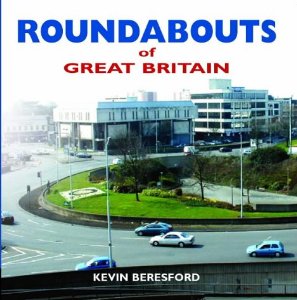

Compare this to the picture of 20th century cities and towns shown in ‘Roundabouts of Great Britain’: endless standardised concrete kerbs, health-and-safety conscious multiplicities of road signs, match-your-neighbour planning department sensibilities. The stultifying effect of regulation is to create uniform places instead of regional vernacular, bureaucratically-scaled decisions trumping human-scaled choices, and slow development instead of fabric that’s responsive to life and use.

In the last 20 years advocates such as Richard Rogers (in his ‘Cities for a small planet’) have started a debate that has changed prevailing views away from car-oriented development by highlighting the downsides of it’s resultant low-density places (though the message has yet to reach many a council’s Roads Department).

It’s time we started a similar debate about about the impact of regulation on architecture. I for one, long for the day that we can make organic places once again.